The Electronic Intifada 28 August 2025

The BBC’s Gaza coverage is not only embarrassing, it is placing interviewees in danger.

AvalonIn addition to scrolling through the devastating daily news on her social media account and helping her family with the exhausting essential everyday chores, Lamis, a second-year university student, is also pursuing her studies in English language and literature in her bleak and somber house in Nuseirat refugee camp – an area that has been heavily pummeled throughout the ongoing Gaza genocide.

In May, the 20-year-old – who, like every other subject in this article, did not want to give her real name – was contacted by BBC World News to do a live interview about the expansion of ground operations in the Gaza Strip. Lamis was excited for the opportunity to present her lived experience on Israel’s genocide in Gaza freely.

Or so she initially thought.

Like many other BBC interviewees, Lamis and others interviewed for this article were shocked to find not only that their interviews were heavily edited, but that BBC producers asked them questions off air they felt were unethical and could endanger their safety.

“At first, the questions were normal,” Lamis told The Electronic Intifada about the interview itself. “But then the presenter mentioned the ‘parties to the war, Hamas and Israel.’ I rejected this claim and said that the war is not against Hamas; it is against defenseless people, against children, against any voice or any hope in Gaza. This is a genocide, not a war.”

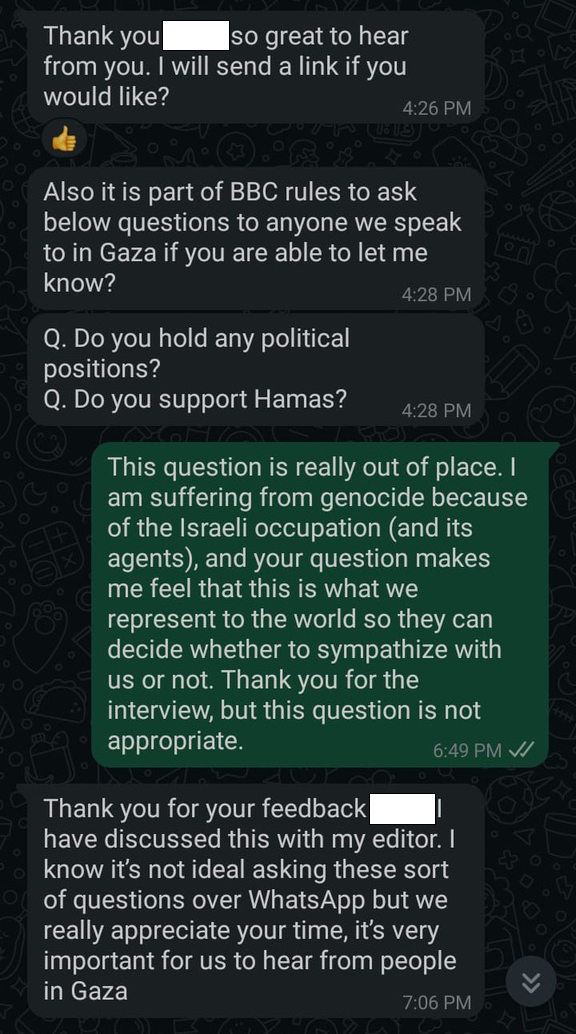

After the interview, the BBC’s producer asked Lamis about her political positions and whether “you support Hamas.”

Aside from the fact that it is commonly known in Gaza that women are not able to join political factions or resistance groups, the questions upset Lamis for several reasons.

“I felt it was unjust,” she said. The BBC was trying to decide how to treat her, she said, and all Palestinians in Gaza based on their political affiliation and opinions.

“Unfortunately, I could not express this because I feared their cooperation with the occupation, and that my answer might put me in danger,” a clearly frustrated Lamis said.

Nevertheless, she told the producer over WhatsApp that the question was “not appropriate,” and was clear with the producer that the cause of the genocide was “the Israeli occupation (and its agents).”

She also feared, she said, that if she proclaimed herself supportive of Hamas, or said any of her relatives were that way minded, that information would make its way to Israeli intelligence.

To compound matters further, Lamis then realized that the interview, when it aired, had effectively been censored to take out any mention of genocide.

“I was shocked that they cut what they wanted. They are showing the world something different from what we are living. They are exploiting us for their own aims,” she told The Electronic Intifada.

“Do you support Hamas?”

Israel has long been clear that it wants to “eliminate Hamas.” Whole families deemed to be affiliated with the resistance movement – often through AI targeting algorithms – have been wiped out.

Excerpts from a WhatsApp conversation between a BBC producer and a potential interviewee in Gaza.

And the slaughter of journalists – who ought to enjoy protected status under international law – continues unabated along with Israel’s genocide. In August alone, Israel has killed 11 journalists, six on 10 August, and another five on 25 August.

The pattern of assassination – as in the case of Al Jazeera correspondent Anas al-Sharif, one of the journalists murdered on 10 August – follows a media smear campaign against targets with fabricated information, often accusing the target of links with Hamas.

Moreover, via Israeli cyber spying and the willing cooperation of social media companies like Meta and Google, the Israeli military is certain to have monitored Anas’ movements and activities. And Israel can do this with anyone in Gaza.

Not only do BBC interviewees fear that by expressing any support for anything Hamas does or says, they and their relatives could wind up as AI-determined military targets, they balk at the ethics of such questions.

Shadin from Gaza’s Deir al-Balah received a message from the BBC in May, requesting an interview and asking the 18-year-old to convey her pain and ambitions for the future.

“At first, I was genuinely proud,” Shadin told The Electronic Intifada. “It felt like an important opportunity to be heard, to speak for my people, and to share our reality with a wider audience through one of the world’s most well-known media platforms.”

She did the interview and was pleased with how it went, only to be asked later: “Do you support Hamas?” The question, from the BBC producer, came under the guise of “integrity and transparency,” and is part of the BBC’s “editorial guidelines” on whether to include an interview in a BBC program.

Pushing a narrative

Shadin never responded because, after seeing the questions, she felt herself in grave danger. Israel’s intelligence agencies are monitoring everything they can, including calls and messages, and Israeli tech companies are world leaders in clandestine software that monitors a target’s movements, calls and online activities, known as spyware.

“As soon as the Hamas question came up, I realized this wasn’t really about us, or about our suffering and survival,” Shadin said. “I felt they were pushing a political narrative. It was disappointing and made me feel unsafe. I knew then that I had to be very careful.”

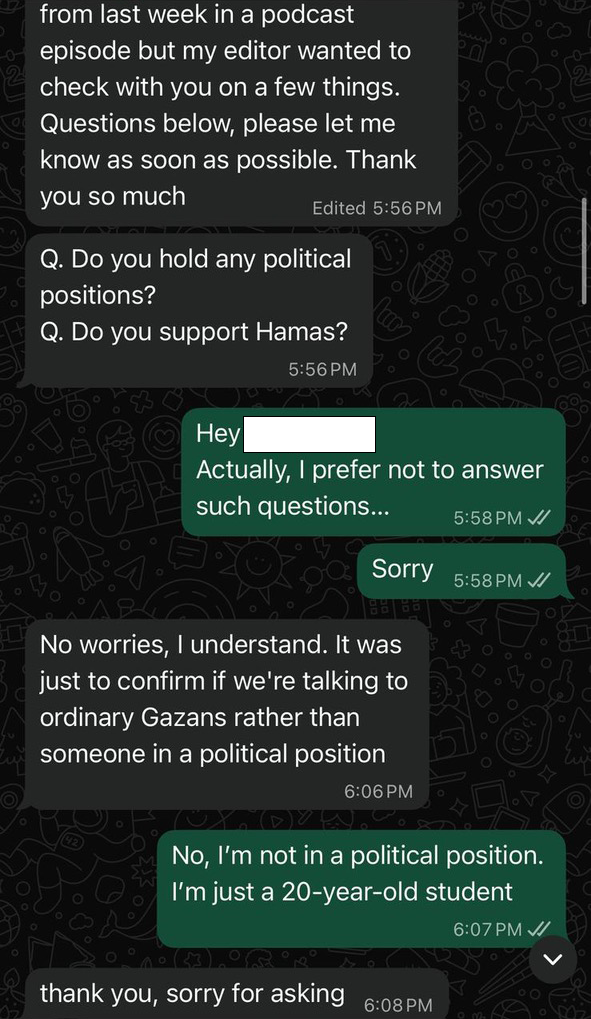

Excerpts from a WhatsApp conversation between a BBC producer and a potential interviewee in Gaza.

Later in June, the same BBC producer who had reached out before, sent another message to Shadin to ask for an interview. Shadin ignored it.

Rima, 20, another Gaza-based writer and student and a friend of Shadin’s, had a similar experience with the BBC.

She did a live interview in May about food shortages in Gaza. A week later, the producer messaged Rima to check – like the others – on her political affiliations.

Rima apologized that she would prefer not to answer such questions. The producer – stretching credulity – argued that she just wanted to confirm they [BBC News] were talking to “ordinary Gazans rather than someone in a political position.”

Rima told The Electronic Intifada she felt like her words didn’t really matter and that the BBC was just discriminating against Palestinians.

“Supporting or opposing Hamas shouldn’t determine how people are treated or whether they deserve to be heard.”

In July, Khader, 17, was contacted in Gaza by BBC News for an interview with the network. The high school student, stranded in a dilapidated tent in the Mawasi area of Khan Younis with his family after the destruction of their house, was excited to prepare for his first live TV appearance.

But out of the blue, the producer asked him, “Do you or your parents have any political affiliation with Hamas?”

The question irritated the teenager and made him uncomfortable.

Dehumanizing Palestinians

Unlike the other young people interviewed for this article, however, Khader responded: “We are against the violence, so no.”

He answered despite the common knowledge that, as with women and political party affiliation, it is generally understood that a child cannot join the resistance in Gaza.

Israel has compulsory military service, and young Israelis, 18 and over, not only have to serve their time, they also get called on reserve duty until they are in their 40s.

It’s the opposite of Gaza, where joining resistance groups is entirely optional, and under-18s – as per the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (OPAC), which was later approved by the UN General Assembly as an addendum to the Convention on the Rights of the Child – are forbidden to affiliate with any of them.

Nonetheless, the BBC producer had no qualms asking Khader about his politics and that of his family. This was done in spite of the well-known shortcomings in the security and privacy of text-messaging apps, particularly WhatsApp, which in January announced that some of its users had been targeted by an Israeli spyware company, Paragon Solutions.

That is, in fact, the reason he felt in peril by the BBC’s query, asked over WhatsApp.

The four young people felt imperiled by the BBC’s dangerous questions and all now wish the BBC had never communicated with them.

This journalist has also faced a similar experience. In fact, on 10 August – the day Israel killed Anas al-Sharif and five colleagues in the Al Jazeera tent by Al-Shifa Hospital – the BBC World Service sent me a request for a pre-taped interview to hear my reaction to the killing of athletes in Gaza and the lack of international support from UEFA and FIFA for our sports bodies.

I was clear with their producer about my thoughts on the BBC. “You’re a mouthpiece for Zionism and you have oceans of the blood of my people on your hands.”

For the past two years, the BBC, along with most, if not all, Western mainstream media organizations, have been deliberately dehumanizing Palestinians and ignoring our plight. They have effectively been manufacturing consent for Israel to go ahead with its genocidal campaign in the besieged territory.

The BBC continues to platform Israelis, including military and political officials. So far, there is no suggestion that the BBC is investigating the political preferences or affiliations of its Israeli interviewees. Certainly, the BBC has never asked them whether they, their parents, their grandparents or siblings have participated in the genocide Israel is perpetrating in Gaza.

From Gaza, the message to the world’s media that the BBC and others continue to ignore despite its irrefutability, is simple.

“Our reality is painful, but it’s real. Don’t look away. Don’t soften it. Let people feel it as it is,” Shadin said.

Abubaker Abed is a journalist and translator from Deir al-Balah refugee camp in Gaza.

Add new comment